Delegate from the Philippines demonstrates her prowess at balancing objects on her head; Japanese beekeepers gather at the Honey Bar

At the registration for Terra Madre, small pins were passed out depicting the silhouettes of a farmer and a soldier, with an equals sign between them. In many ways, this icon summarizes what Terra Madre is about. It is a gathering of food communities and food producers, and a strategy session on how best to battle the onslaught of industrialized food, environmental degradation and social injustice. (Update: I’ve learned that the pins are from Slow Food Nation, and actually depict farmer = Statue of Liberty. Apparently I glanced at it too quickly.)

The opening ceremony is reminiscent of the Olympics, partly because it takes place in the Palasport Isozaki, an arena built for the 2006 Torino Olympics. Rather than athletes though, the crowd was cheering for farmers, fishermen, chefs and researchers. With much fanfare and applause, representatives from 160 countries paraded into the stadium carrying their nation’s flags. They were accompanied by a youth choir and orchestra that had been set up in the stands, complete with several harps and a marimba. This was followed by a series of speeches by representatives of indigenous peoples, such as the Guaranì of Brazil and the Kamchadal of Russia.

At last, Slow Food founder and figurehead Carlo Petrini took the stage. “The principal custodians of traditional knowledge,” he said, “are the indigenous peoples, the farmers, the women and the elderly, the very categories that today’s institutions and media pay the least attention.” He went on to address the students in the audience. “You have been given a grand opportunity to reconcile science and modern technology with traditional knowledge.” Petrini declared that the conference had officially commenced, as the crowd roared and leapt to their feet. The last time I was in a crowd this excited was at the Obama rally in Chicago on election night.

Aerial view of the Terra Madre conference hall

There were certainly members of food-world royalty amongst us. Berkeley organic movement matriarch Alice Waters was present, for one. Then, I was extremely thrilled to see Fuchsia Dunlop, author of the seminal texts on Sichuan cuisine, Land of Plenty and Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper. She was acting as a translator during a presentation from one of the Chinese delegates.

For the most part though, this is a conference populated by average, everyday people who simply share one vision. Sometimes it is a serious academic affair, while at other times, it takes on the air of a party or pep rally. During the regional panels, I was sitting at the Asia meeting, quietly listening to a presentation on Malaysian Bario rice, when applause and hoots from across the hall filled the air. What on earth is going on over there? It must be the Americans. Either that, or the youth food movement delegates. I packed up and sprinted over to the US meeting, where Petrini was addressing the crowd. “I want to thank you for your hospitality and hard work,” he said. “In the United States, the revolution has not just begun, it is underway.” The room exploded with cheers.

Back-thumping festivities aside, the core of Terra Madre is a series of research presentations on a wide-range of topics, such as water scarcity, principles of fair trade, food packaging design, and seed ownership and patent rights. In particular, the World Watch presentation included some novel ideas on how to sustainably fight poverty, like creating pay incentives for farmers who store carbon in their soil.

Outside of the seminar rooms, there were a number of exhibits on sensory analysis and biodiversity. There was a Honey Bar, with over two dozen kinds of honey from around the world, including chestnut, orange flower and chestnut honeys. However, the most exotic product was a Japanese honey that contained whole hornets. Apparently, the hornets attack and kill honeybees, so enterprising beekeepers now use them to er, flavor the honey instead. I asked what was done with the hornets after the honey had been consumed. “Oh, you can eat them! Preferably with whiskey,” replied the Japanese beekeeper. “Or, they are also good if you twice-fry them.”

Not too far from the Honey Bar, a large billboard titled “Discovering Biodiversity” had been set up, and people were instructed to write down the name of a product from your country in your mother tongue. “But wait, what’s my mother tongue?” I asked in confusion. “I was raised with one language and educated in another.” Danielle replied confidently, “It’s the very first language you learn.” After the marker was passed to me, I scribbled 紅豆 (red beans) onto the wall. In retrospect though, it would have been more appropriate to write something like 漢堡包 (hamburger).

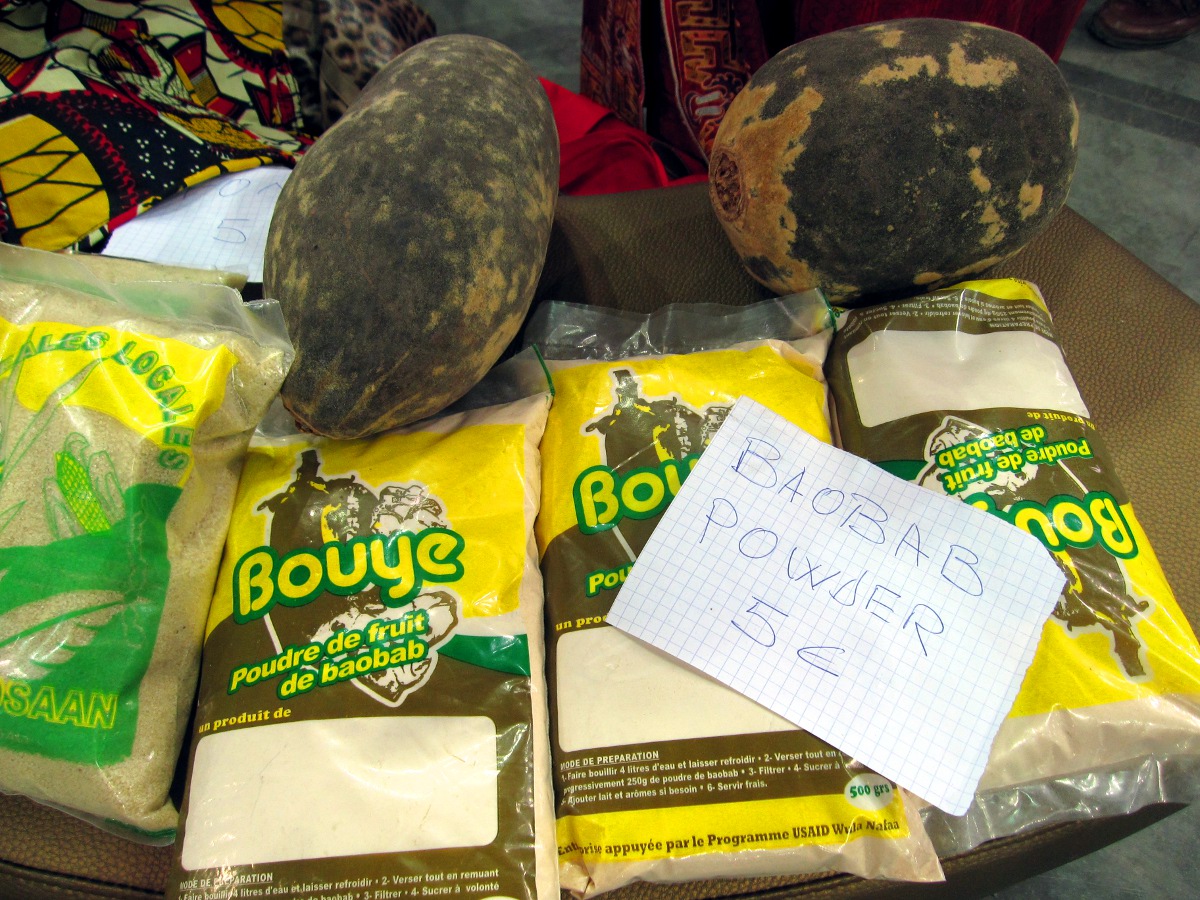

Elsewhere in the main atrium, an open-air bazaar had spontaneously sprung up. Atop overturned boxes and colorful carpets, delegates were hawking goods from their native countries, selling everything from hand-dyed scarfs to dried hibiscus flowers to lemongrass plants with the roots still attached. There were a number of spices I had never seen before. (Clearly Italian customs are not as stringent as American customs, which would have never allowed many of these food products to enter the country.) The market is not officially sanctioned by Terra Madre conference organizers, but it seems like the tradition is broadly accepted, if not silently encouraged. For the first time, I could buy an African bag and know that the money would actually support the people who need it.

The next Terra Madre will happen in 2012, but plans are in the works for a Terra Madre-style convention to take place in New York City in 2011. Maybe I’ll be there next year wearing another “organizer” badge?