Nights in culinary class move in a dance of steel and time pressure. Yank out the wishbone. Quarter the chicken. Sear the skin. Chop the mirepoix. Simmer the stock. Strain the sauce. Pull the chicken from the oven. Plate the food. Run to the front. Hope for the best.

Chef Ray glanced at my plate of poulet sauté chasseur (hunter-style chicken) and gave me a hard look. “I think I’ve told you this before,” he said. “This plate. What’s wrong with it?” I looked down at my chicken. Among the finely shredded flakes, there were some unruly tufts of parsley perched on top, shamelessly advertising their prowess at escaping my knife. “I know, I know,” I apologized, “the parsley isn’t chopped small enough. And there’s some pieces of stems.”

With a spoon, he pointed at a resolutely intact parsley leaf. “Look,” said Chef Ray, “you spent two hours making this dish, and you put herbs like this on the plate it and it just ruins the presentation.” He chased the offending chunk of parsley to the edge. “The chef that taught me insisted on really finely chopped herbs, so since that’s how I was taught, this is a pet peeve of mine too.” Chef Ray prodded at the chicken. “This is cooked well, it’s not overdone and the skin looks great. But you put parsley like that on the plate and that’s the first thing you see.” I bowed my head. “Yes, Chef.” He sighed. “All right, start cleaning up.”

God damn it, I hate chopping herbs.

You know what it looks like when Chinese people chop herbs? Like a lawnmower belched huge piles of foliage on the table. And that’s perfect. We embrace chunky cilantro and scallions like Sir Mix-a-Lot loves chunky booty. Let me show you some examples:

Here’s a plate of Five Spice Beef from China House in Mountain View. It looks like they didn’t bother chopping anything, they just threw entire stalks of cilantro on the plate.

Maybe we need to look at a better restaurant? Cult favorite Mission Chinese Food in San Francisco has won all sorts of awards, so let’s take a look at their mapo tofu. Yup, you can definitely see big pieces of leaves and stems floating on that chili oil.

And my personal favorite, Double Cooked Pork from Happy Kitchen in LA. THEY ONLY USED CILANTRO STEMS!

Let’s review the most common culinary school sins:

- Plate not hot enough (forgot to put it in the oven)

- Plate too hot (forgot to take it out of the oven)

- Sauce underreduced and not nappant (sticks to the back of the spoon)

- Sauce overreduced and too thick

- Vegetables not brown enough or too brown/burnt

- Meat under or overdone

- Vegetables not cut uniformly (see taillage)

- Not enough acid (lemon juice)

- Food not salty enough (I’ve never been told my food’s too salty, even when I try to overseason)

- Too much grease

- Too much sauce (pooling at bottom of plate)

- Sauce drips on plate edge

- Using black pepper in a white dish (where’s your white pepper idiot?)

- And of course, my #1 nemesis, the herb garnish is too big

In other words, no matter how hard you try, your plate is never good enough. Wait, this is starting to sound familiar…

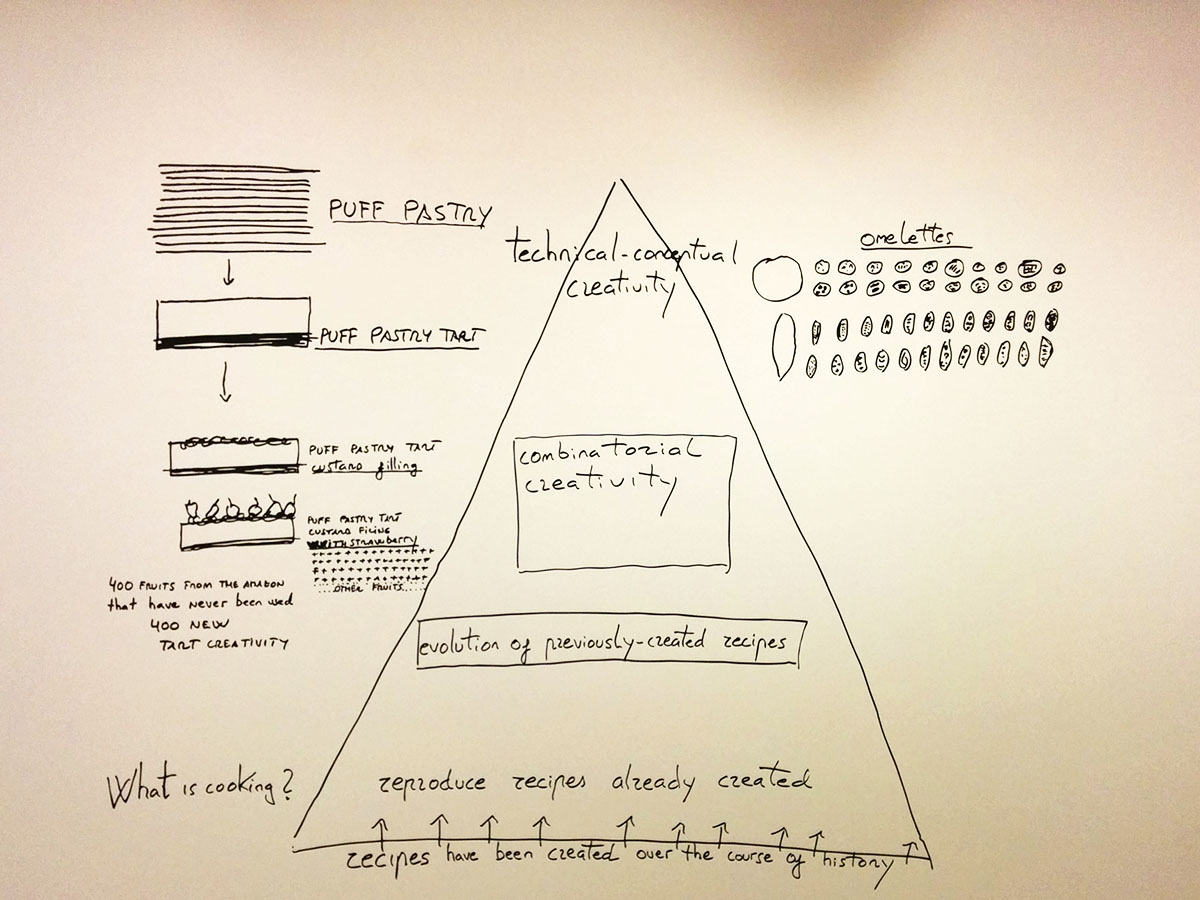

Maybe the solution is to give up on cooking?

At least my extra tournage work at home paid off. Chef Ray looked at my potato cocottes and said they looked great without other comment. Phew.

I can’t even imagine how much of a pressure cooker it would be to compete on TV. (Well, maybe I can. This piece from pastry chef Allison Robicelli is a hilarious read if you’d like to hear more.) I would have a nervous breakdown. Or start pouring fish sauce on the judges’ cars.

Whatever. My new favorite food photography blog is now Dimly Lit Meals for One (exactly what it sounds like).

Clearly the solution is to start chopping like this guy: