In the locker room, we carefully unpacked the contents of our tote bags. Crisp white jackets with cloth knot buttons, wide-legged houndstooth pants and a cap to keep stray hairs in place. I carefully slipped the knots on the jacket in and out of the loops; it was a long, laborious process. “Wait a minute,” said the girl down the aisle, “The jackets are big enough that you can put them on without untying the buttons!” At the bottom of my bag, a neatly folded triangle of white cloth remained. “Is this a side towel? Or a napkin?” I asked. “Actually, I think it’s the neckerchief,” another student replied. “But I have no idea how to tie it on.”

I decided to shove my neckerchief in my pocket and go into the hallway, where the rest of my classmates were waiting. Some were chatting, some pacing, others taking selfies with their phones. Photos of famous chefs loomed behind us, and the Wall of Fame on the opposite side was decorated with the hand molds of renowned chefs. Eric Ripert, Thomas Keller, Bobby Flay and more. It was a reminder that the ICC is a living museum of food industry titans. Would any of us be future culinary superstars?

Inside our designated kitchen, Chefs Ray Dawson and Janet Crandall greeted us with smiles. Chef Ray introduced himself and explained that while we were off to a late start on the first day, he would expect us to be prompt in the future. “When I ask you to do something, you should show that you understand by responding, ‘Yes, Chef!’ Is that clear?” he said. “Yes, Chef!” we chorused. He began by guiding us through the proper way to tie our neckerchiefs. Cross the right hand over the left, switch hands, bring the right side over, loop it under and inside the knot. Let’s hope I remember how to do this next week.

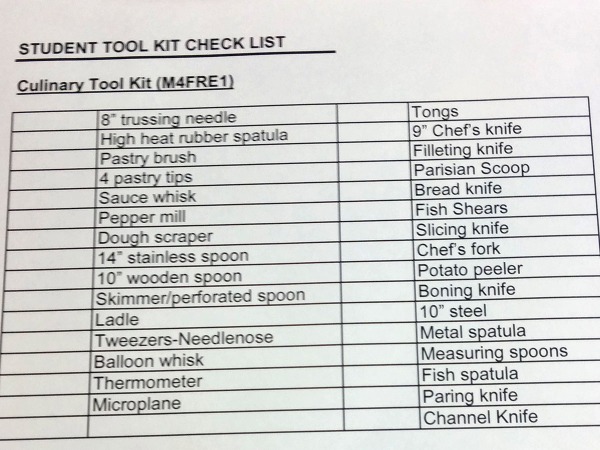

“Some of you will get cut,” Chef Ray continued. “Some of you will get burned. Don’t be embarrassed, just tell us immediately and we’ll decide how to help you.” He began explaining each of the knives and tools in our kits. A chef’s knife, a slicer, a serrated knife, a boning knife (sturdy and firm), a fish knife (thin and flexible). A channel knife for citrus twists. Tweezers for removing fish bones. A Parisian scoop, aka a melon baller. It was as if Christmas had come early! I suddenly had tons of tools that I’d always wanted but couldn’t justify buying. In the corner of the room, a student cut himself while removing a knife from its guard. Chef Janet rushed over with a bandaid.

“Let’s talk about equipment,” Chef Ray continued. “This is a half sheet pan and a full sheet pan. This is a hotel pan, and these are square boys. You can fit 6 of them into a hotel pan. This is a russe (straight-sided sauce pan), this is a marmite (tall stock pot) and this is a sautoir (sloped sauté pan).” Although the school had changed its name away from being the French Culinary Institute, it was evident that French conventions were still the rule.

After more warnings about the importance of sanitation (“do not use your fingers to taste something”) and safety (“you’re probably going to burn yourself in this class”), we launched into taillage, the art of uniform knife cuts. “Why is this important?” asked Chef Ray. “Two reasons: aesthetics and even cooking. The food will look great and be done at the same time.” He went on to expertly dice and mince a series of onions, carrots and turnips into precise pieces.

It was our turn to try out our new knives. I’ve been using a thin, straight, single-edged Japanese knife at home, so picking up a Western-style chef’s knife felt bulky. “Try to slice in a single motion instead of sawing back and forth,” said Chef Janet, as I struggled to ciseler my onion. Next, I tackled the carrot, squaring off sections and cutting rectangular tranches. Each tranche must be cut into long strips, then diced into uniform cubes. I showed my macédoine to Chef Ray. “Not bad,” he said, “but these are a little uneven, and a little too small. You’ll get there!”

I began trimming my vegetables more aggressively to get the most uniform shapes possible. My hefty turnip was soon whittled down to a small handful of fine brunoise cubes. “Well done!” said Chef Janet. The pile of vegetable trimmings left over was immense. I realize that I am an amateur at this, but I can only imagine that fine dining kitchens still generate a large amount of waste food scraps. At the ICC, we carefully saved all the onion and carrot trimmings for making stocks, however all of the turnip pieces went to compost because there was no way to use so many turnips.

We took a break for dinner, cooked by the level 4 students, then returned for the second half of class, a demonstration of cooking à l’anglaise (ahead of time) and à la minute (on the spot). As my partner and I were cooking our second batch of carrots, we left a pan on the burner for a little too long. When he added the carrots to the pan, the butter flared up and flames shot toward the ceiling. My partner’s arm shot out and he twisted the burner knob down. The flames subsided and I looked around. Neither of the chefs had noticed, and the carrots didn’t seem any worse for being lightly flambéed. We presented our plate to Chef Ray, and I apologized for the carrots being underseasoned. “I think they’re seasoned fine actually,” he said, “however, do you see this butter pooling on the bottom of the plate? We’re not focusing on presentation yet, but in the future, you would want to drain the carrots on a paper towel to prevent that.”

Next week: stocks, sauces, and inventing a square turnip.