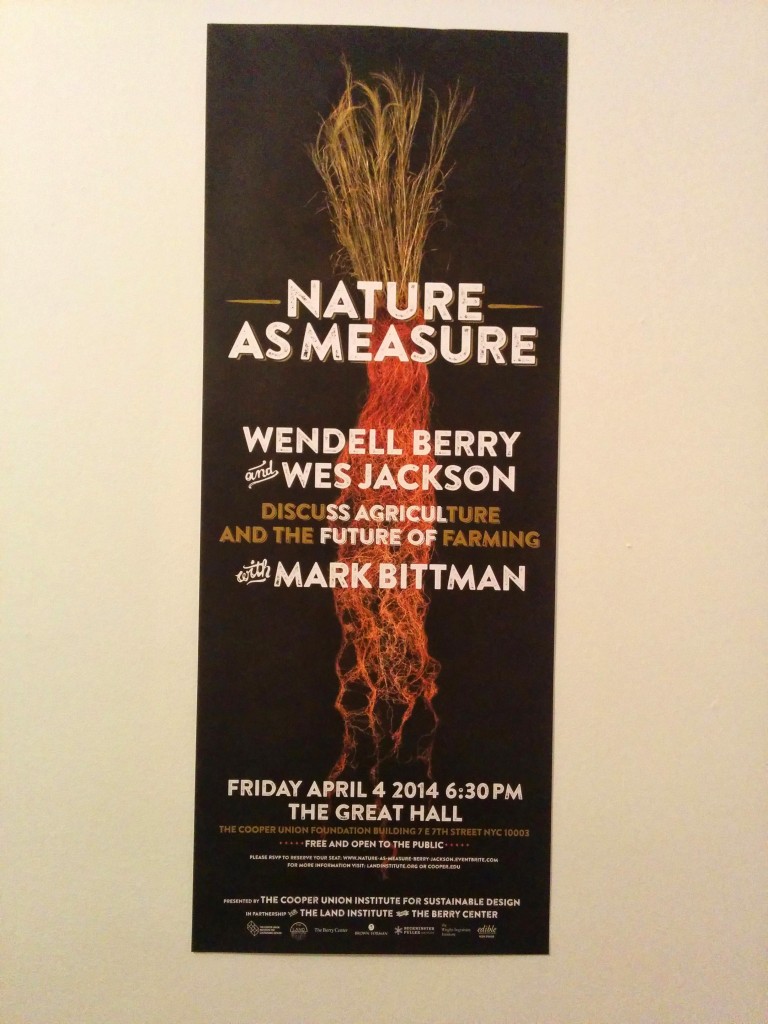

Tonight, some of the biggest names in the sustainable food movement gathered in the Great Hall at Cooper Union. The occasion? “Nature as Measure,” a talk on agriculture and the future of farming presented by the Land Institute and the Berry Center.

If I had to choose a single cookbook for today’s aspiring home chefs, it would be Mark Bittman‘s How to Cook Everything. He first became nationally known through his NYT column “The Minimalist,” which cut through the confusion to teach healthy, painless home cooking. I used to describe Bittman as my generation’s Julia Child, but he has since moved on to bigger and bolder topics: influencing national food policy. I don’t always agree with his pronouncements, but aside from perhaps Michael Pollan, no other American food writer is as well-loved and widely-read as Mark Bittman.

While Bittman is a relatively recent addition to the food politics scene, Wendell Berry is the elder farmer-poet-statesman. If I were to search my inbox for food-related signature quotes, I’m fairly certain that Berry’s soundbites would be the most frequently used. I also have a soft spot for Berry because he hails from my home state of Kentucky. (Bet you didn’t know that I’m a Southern belle!) Berry has been writing and thinking about agriculture for decades now, and channels the oratorical elegance of Lincoln (another KY native) in many of his thoughts:

“The care of the Earth is our most ancient and most worthy, and after all our most pleasing responsibility. To cherish what remains of it and to foster its renewal is our only hope.”

“Not luxury or extravagance for a few, but modest, decent, sustainable prosperity for many.”

And of course, the simple but profound sentence that launched Michael Pollan’s food journey:

“Eating is an agricultural act.”

I’ll confess that I wasn’t familiar with Wes Jackson before tonight, but he is a well-respected agronomist and environmentalist, and a good friend of Berry and Bittman. The warm camaraderie between Jackson and Berry was very much on display, as they joked and bantered with each other like Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellan. It was also really refreshing to hear from thinkers with real world Midwestern farming experience; all too often at these sorts of panels and lectures, you simply have some polished urbanites talking to other canvas bag-toting urbanites.

Not surprisingly, the audience was also full of NYC’s finest agtivists; I spotted Marion Nestle‘s bouffant hair in the front, among other familiar faces.

Much of the discussion explored ideas that I was already familiar with, but one initiative that was new to me was the Land Institute’s research in breeding perennial crops. “We can now build an agriculture based on the way actual ecosystems work, and that’s why our group at the Land Institute is perennializing the major crops so that those roots can be there and hold the soil, and we can put them in mixtures that would mimic the vegetative structure that would give us the processes of the wild to come to the farm,” said Jackson. “And this would represent a fundamental shift in the way we do the business on the landscape. Ten thousand years ago, nature had to be destroyed in order for the seed to germinate. But now with the perennials, we can take all that knowledge that’s been put on the shelf, bring that to the farm, and begin to have an agriculture that is as sustainable as the nature that we’ve historically destroyed.”

Bittman continued by asking what can be done to encourage young people to pursue careers in farming. “I remember my grandmother saying to me, honey don’t ever farm,” said Berry. “It’s because in the agricultural system that we’ve got, the farmer is least considered and lowest paid in the whole structure. This is going to make it very hard to keep the farm-raised young people on the farm. And whether they’re raised in a family that’s farming well or not, they’re still used to being dependent on the weather. They’re still used to getting up in the morning. I was just reading that some of the people in education have decided that it’s unnatural to expect young people to get up in the morning. So they’re going to start school later.” [laughter] “It’s unnatural for any human to get up in the morning and go to work. But there’s a different set of assumptions for humans, and that is that they get up in the morning and take care of their responsibilities. So I’m for starting school earlier!”

I admit that I was hoping for more definitive policy recommendations and ideas from Berry, and at one point, Bittman pressed him to discuss what types of institutional changes he’d like to see. Berry paused for a moment, then lobbed a beautiful rejoinder: “This is the kind of question that I always duck. And I’ll tell you why: because it assumes that I or somebody has a plan. And I don’t have a plan. And I would be a little frightened of anybody who did. I’m suspicious of plans to begin with. I’m suspicious of people who claim to know about the future. I think that the right thing to do now is usually obvious and choices are standing in front of everybody that can be made, but in the whole collection of people and choices, it’s going to be a clumsy business. You don’t start with an agenda of problems and solve them one at a time until they’re solved…So, it’s not going to be a clean—that’s the way Communists think and they always mess up. [laughter] There’s always some final solution that’s being proposed and it’s always messed up. And that’s because we’re human. And so what I think we need to become is better critics. We have to have a better standard, and that standard is nature. Nature’s going to give us the standard, and then we begin to judge our solutions, we begin to judge the steps we’ve made, we begin to work our way. Slowly, humbly and alertly. And pleasingly towards a better way.”

So, what can we city slickers do to ease progress towards a better way? Berry mused on the rural and urban divide for a moment. “Industrial agriculture is an urban invention after all. Country people didn’t invent it; it was sold to them. Bad deal, but they bought it. And if we’re going to have a better agriculture, it’s going to come about, to a very large extent, because urban people become informed enough and concerned enough to help us invent a better agriculture and to insist that the necessary things be done.

“In saying that, I think I’ve taken a step beyond the old competitive model. We’ve assumed—too easily—that the country was in competition with the city, that humans were in competition with nature. We’ve assumed that the producer and the consumer are in competition, and there’s just a better way. I think that a good name for the better way is the neighborly way. Who are your neighbors? Your neighbors are the people who need your help.”

It’s a thought worth remembering in a metropolis that often values screens over smiles.

Oh yes. This was wonderful. I am pretty much in love with Berry.

Were you at this talk? He was super cute, it was like meeting Sustainable Agriculture Santa Claus. 🙂